Terminal Color Sequences

Everyone likes a little bling in their terminals, come on. I personally like decorations that are on the minimal side, so I like to render colored output.

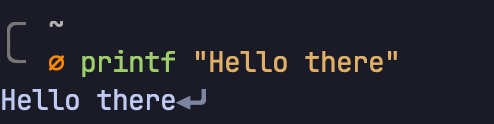

The simplest thing you can do is print text to your terminal:

$ printf "Hello there"

(I’ll use the printf command instead of echo in this post because it is friendlier

to terminal escape sequences out of the box)

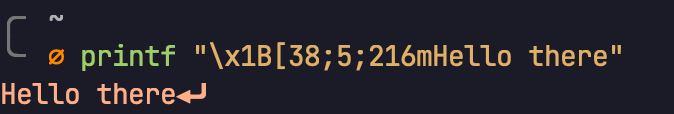

The other option you have is to render this text with some color (say orange):

$ printf "\x1B[38;5;216mHello there"

Whoa, let’s break this down. The first character is\x1B, this just marks the beginning

of an escape sequence. It tells the terminal that the following few characters

aren’t meant to be printed. The terminal knows how to interpret them.

The next section of the escape sequence is [38;5;. This tells the terminal that

we want to change the foreground color of the text that follows this escape sequence.

The next section is an 8-bit number, 216 in this case. 216 represents an orange-ish

color. All I did was look up a color I liked from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ANSI_escape_code#8-bit,

and hooked up its number in here. This wiki page might be an interesting read for

people curious about the history of terminals, but the TL;DR is that most terminals

today support 8-bit colors only, so we’re limited to 256 colors. Some terminals

(like Kitty) support a much wider range, which gives you more color options. This

is how they’re able to render whole images!

Alright, the next section is the letter m, this marks the end of the escape sequence.

What follows is some text that we actually want to print (which is Hello there

in our case). Run this, and bask in the glory of rainbow text!

It is important to note that the color you set applies until you either set a different foreground color, or you reset it. I’ll talk about this at the end.

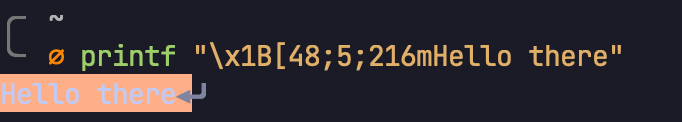

There’s much more we can do. For example, we can set the background color of characters using this:

$ printf "\x1B[48;5;216mHello there"This will look extremely similar, but you’ll notice that the second part of this

“magic string” is [48;5; (instead of [38;5;). This sequence tells the terminal

that we want to change the background color of the text that follows. The rest

should be recognizable, I’m using the same orange color as before (216)

(Little hard to read because of the contrast, but try it yourself!)

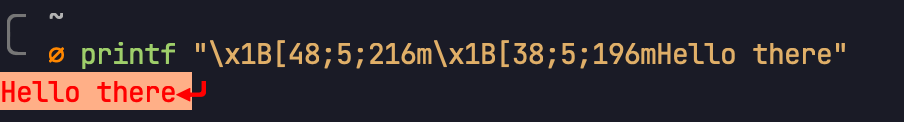

So if you want to combine the two now, you can render red text on an orange background this way:

$ printf "\x1B[48;5;216m\x1B[38;5;196mHello there"

You’ll notice that I used two separate escape sequences, one to set the foreground color, and the other to set the background color. You can’t set both of them in one go.

There’s more! You can even change the style of the text (aka make it bold / italic / underlined). You do this by appending a single number after the color. For example, this renders underlined, orange text:

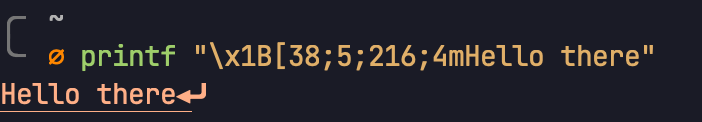

$ printf "\x1B[38;5;216;4mHello there"

You’ll notice I added a ;4 after the color. 0 is the default, 1 represents bold,

2 thins the text, 3 italicizes it, and 4 underlines it. Try them out!

The general format of an ANSI escape code (that’s what these are called) is this:

\x1B[38m;$number;$stylem // Foreground

\x1B[48m;$number;$stylem // BackgroundThis knowledge is universal! The coloring is done by your terminal, so it doesn’t matter what language you’re using. The next time you want pretty terminal output in a Bash script, or a JS app, there’s no need to reach for a library!

This is how far you can take it:

This is from a terminal greeter I wrote for myself: https://github.com/sdnts/zfetch

Here’s a bonus tip: you can reset the foreground/background color by using the number

0 as the color value. You know how some programs will mess up your terminal

output when they exit / crash? Normally, the program’s author will take care to

“reset” these terminal colors when it exits, but they might not apply when the program

crashes. So you might notice that your cursor is gone, or the foreground colors

are all messed up. I’ve set up this (fish) alias to reset terminal colors, which proves

itself useful every few days (I’ll leave it to you to investigate how it works):

$ abbr clear 'printf "\033[2J\033[3J\033[1;1H"'Or, for bash/zsh folks:

$ alias clear='printf "\033[2J\033[3J\033[1;1H"'