Demystifying CORS

I’ve been making chages to R2’s CORS implementation this week, and now I think I know more about CORS than anyone really needs to know, especially how S3 implements it 🤮. It gets a bad rep. At its core, it is a remarkably simple, and dare I say elegant system — it’s the edge cases that do it in. [CITATION NEEDED]

Before we even begin, the most important thing to realize is that CORS is orchestrated

entirely by the client, which in most cases is a web browser (or things emulating

web browsers). You can bypass CORS entirely by just using curl to make your HTTP

request. But we’ll see later why this isn’t as big a deal as it sounds. In the rest

of this post, I’ll assume we’re in a web browser.

The core idea is that a server should be able to control who can interact with it. This can be useful for security, privacy, or to prevent abuse — all with the caveat that it can be bypassed easily, but I won’t keep mentioning it. CORS is also no substitute for proper authorization, again, because it can be easily bypassed.

CORS stands for Cross-Origin Resource Sharing by the way. example.com and localhost:3000

are examples of “origins”.

How does it work?

The best way to learn how CORS policies work is to build them yourself, so we’ll do that. If you’re in a hurry, skip to the TL;DR.

So say you’ve got a server up on userstore.com that exposes three endpoints:

HEAD /usersreturns the number of users registered on your serviceGET /userslists all usernamesPUT /userscreates a new user

You’re talking to it from localhost:3000. You write some JavaScript to send it a

HEAD request to get the number of users:

const count = fetch("http://userstore.com/users", {

method: "HEAD",

});

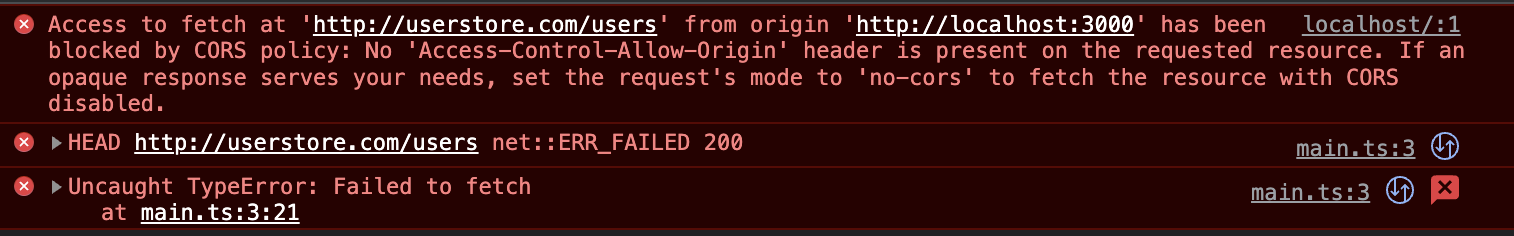

console.log(`We have ${count} users`);Run this, and you get hit with the classic

Access to fetch at 'http://userstore.com/users' from origin 'http://localhost:3000' has been blocked by CORS policy: No 'Access-Control-Allow-Origin' header is present on the requested resource. If an opaque response serves your needs, set the request's mode to 'no-cors' to fetch the resource with CORS disabled.

So many new terms!

userstore.com and localhost:3000 are different origins, and as such the browser

is preventing localhost:3000 from accessing resources (in this case, the /users

endpoint) from userstore.com. The browser is preventing sharing resources across

origins. The browser is preventing Cross-Origin Resource Sharing. You see where that

acronym comes from?

By default, browsers assume that JavaScript on localhost:3000 has no reason to

make requests to userstore.com, because they’re different websites. This is an

important security measure to ensure that there’s more standing between your pizzeria

and your bank account than a measly fetch request.

But if you control both domains and actually do want them to be able to share resources, you can set up a CORS policy on your server, which is fancy-talk for defining what kind of clients are allowed to talk to your server, and what kinds of actions they can perform. We’ll do this as we go along. If you’re in a hurry, skip to the TL;DR.

Getting HEAD requests to work

To really understand what’s happening, our fetch call isn’t going to help us much,

so let’s look at the raw HTTP request that went out:

HEAD /users HTTP/1.1

Host: userstore.com

Origin: http://localhost:3000(In HTTP, the Host header tells you where the request is headed, and the Origin

header tells you where it is coming from. Your fetch call sets the Host depending

on your url parameter, and your browser sets the Origin header. JavaScript

cannot control the Origin header, so it is always accurate)

And here’s the response that came back:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json

10Huh, looks like the server responded with a 200 and the number of users, and

yet our JavaScript didn’t get this response.

What’s happening here is that the browser is intervening. It looks at the response,

sees that there is no Access-Control-Allow-Origin header, and thinks the server

does not want the current origin to be able to read this response. This is exactly

what the error also says, if you read it again:

Access to fetch at 'http://userstore.com/users' from origin 'http://localhost:3000' has been blocked by CORS policy: No 'Access-Control-Allow-Origin' header is present on the requested resource. If an opaque response serves your needs, set the request's mode to 'no-cors' to fetch the resource with CORS disabled.

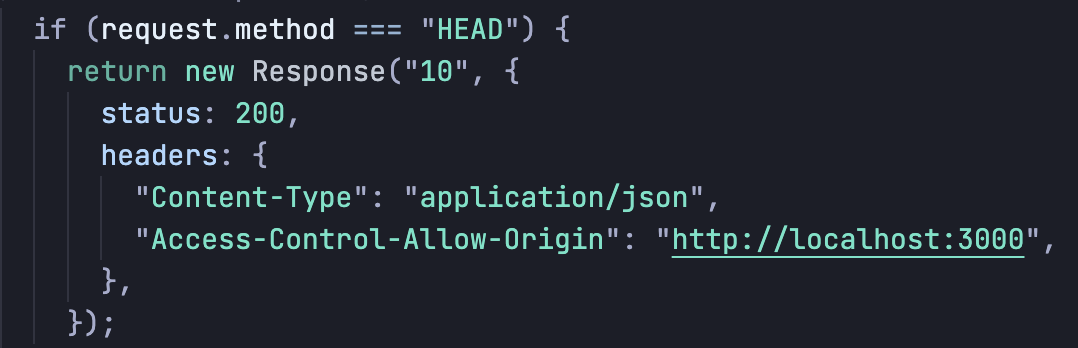

So let’s help the browser out, let’s go to our server (userstore.com), and set

the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header to the format it needs:

Our request/response pair now looks like this:

HEAD /users HTTP/1.1

Host: userstore.com

Origin: http://localhost:3000

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: http://localhost:3000

Content-Type: application/json

10That was it! We no longer see a CORS error in our browser, and we’re able to read

the response of our HEAD request in JavaScript.

Our server told the browser that it was okay to let localhost:3000 access the

resource in question (in this case, the /users endpoint), and the browser acknowledged,

letting our JS access the response’s body. We’ve just set up a CORS policy. The cool part about this is

that the browser didn’t have to make a separate request to ask the the host (userstore.com)

which origins are allowed to talk to it, it just piggybacked off the actual HEAD

request. Just to be crystal clear, our JavaScript hasn’t changed:

const count = fetch("http://userstore.com/users", {

method: "HEAD",

});

console.log(`We have ${count} users`);Super important to realize: CORS policies are set on the server! There’s nothing a client can do if it is seeing CORS errors, and this is by design.

Sick, so this was simple, all we had to do was set a single header in the server’s

response. Let’s try to get our PUT / GET requests working next.

CORS Preflights

Let’s wade into the (apparently) more confusing parts of CORS. We want to now try

and get our PUT request to work, so we modify our fetch call:

const count = fetch("http://userstore.com/users", {

method: "PUT",

headers: {

"Content-Type": "application/json"

"User-Id": "11" // This header is added for demonstration only, it'll become clear why in a bit

},

body: JSON.stringify({ username: "user10" }),

});

console.log("Created user with id 11");

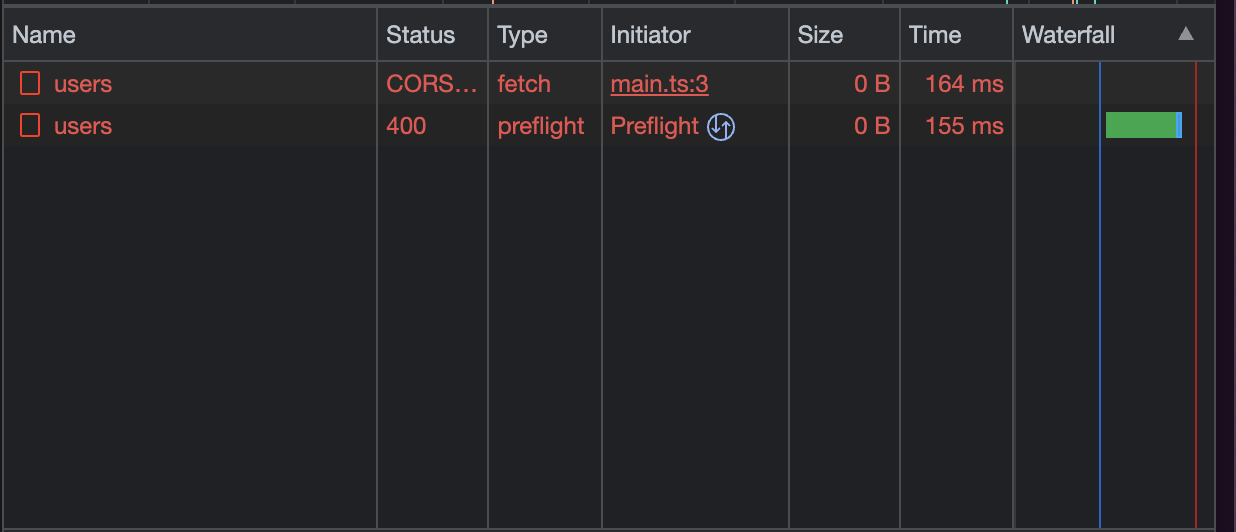

Er, what? It looks like our one fetch call actually

ends up creating two network requests. If we investigate, one of them has a Type

of preflight, and the other one is a fetch. The preflight request has the

HTTP method OPTIONS. This is, of course, expected behaviour.

When it comes to CORS, all fetch requests are classified into two categories:

“simple” and “preflighted”. The browser decides which category your request belongs

to, but in general, requests that might cause server-side mutations are preflighted,

and others are considered “simple”. In our case, the browser decided that the HEAD /users

request was “simple”, but the PUT /users request isn’t. How the browser makes

this decision is covered later.

Think about this: The whole idea behind CORS is that a host server (userstore.com) defines the origins (localhost:3000)

that are allowed to access it. Because CORS is orchestrated entirely

by the client, what actually happens is that the request that your browser sends

is processed by the server, but the response to that request may not be made available

to the JS that requested it. So sure, for a HEAD /users request, the server returns

the number of users, but your JS may not be allowed to read the response that contains

it, depending on the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header, like we saw in the

previous section. But this becomes problematic when your fetch asks the server

to do mutations, like deleting an existing user. The browser cannot just send a DELETE /users

request and deny the response to JS, because the JS succeded in doing what it wanted,

it deleted a row from the server’s database. The fact that the browser denies reading

the response to the JS doesn’t matter, the damage is already done. In these cases,

the browser must explicitly ask the server if the request it intends to send is allowed.

It does this using a preflight request. If a preflight request fails (returns

anything other than a 2xx status code), the actual request is not sent at all.

So let’s look at this preflight request. This is what it looks like:

OPTIONS /users HTTP/1.1

Host: http://userstore.com

Origin: http://localhost:3000

Access-Control-Request-Method: PUT

Access-Control-Request-Headers: User-IdSo if the idea behind this preflight request is to explicitly ask the host (userstore.com)

if a request is allowed, this OPTIONS request describes the request that it is

about to send:

- The

Originheader of thisOPTIONSrequest says that the the originlocahost:3000is trying to make this request - The path says that the origin would like to send a request to

/users - The

Access-Control-Request-Methodsays that the origin would like to send aPUTrequest - The

Access-Control-Request-Headerssays that the origin would like to send aUser-Idheader (this is a comma-separated list if there are multiple headers in the intended request). Note that the actual value of the header isn’t sent, just the name.

The server gets these things, decides if the origin is allowed to perform the action

it wants, and then returns a 2xx response status to give your browser the go-ahead.

The browser then sends the actual PUT /users request, with the headers and everything.

Any other status code is considered a rejection, and the PUT /users request doesn’t

go out at all.

So in our case, our server doesn’t even know how to handle OPTIONS request, so

it returns a 400, and so we see a CORS error. Let’s fix that real quick. This is

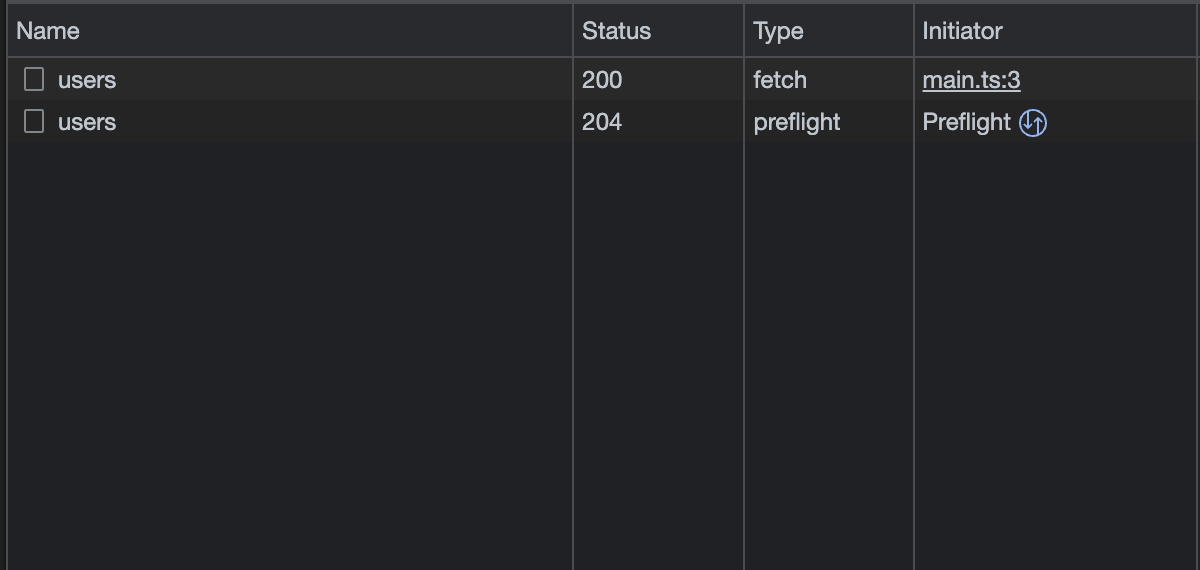

what we want the request / response pair to look like:

OPTIONS /users HTTP/1.1

Host: http://userstore.com

Origin: http://localhost:3000

Access-Control-Request-Method: PUT

Access-Control-Request-Headers: User-Id

HTTP/1.1 204 No Content

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: http://localhost:3000

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: PUT

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: User-IdThe server is explicitly saying that on the /users path,

- The origin

http://localhost:3000is allowed, via theAccess-Control-Allow-Originheader. Note that this is the same header that is used in “simple” requests as well. Also note that the port is part of the address. This becomes important during development! - The method

PUTis allowed, via theAccess-Control-Allow-Methodsheader (this is a comma-separated list if multiple methods are allowed on this path) - The header

User-Idis allowed, via theAccess-Control-Allow-Headersheader

Once the browser gets this confirmation (AKA the status code is 2xx and the Access-Control-*

headers are kosher), the PUT /users request goes out and we do not see a CORS error!

One weird quirk here is that the PUT request’s response must also contain the Access-Control-Allow-Origin

header, even though the browser did get explicit permission from the host server during the preflight.

To be honest, this seems unnecessary, but this is one of the ugly bits of CORS. If

you’re setting CORS up, remember this!

Again, our fetch request is still the same. This is worth repeating: CORS policies

are only set on the server!

Alright now that you know this, please stop setting Access-Control-Allow-Origin

to *! You’re unnecessarily allowing all kinds of actors on to your server!

The ugly bits

So far, things have been kinda elegant, right? The browser tries to minimize the number of requests it sends to your server. If it thinks the request cannot really do any damage (“simple” requests), it piggybacks off the actual request to figure out if the JS that initiated the request is allowed to do it. But if the request seems dodgy, it’ll send a “preflight” request to make sure your server approves the request before making it.

(Of course there’s a huge caveat here that your server is actually following REST

verb principles: only reads in GET requests, create-or-replace for PUTs etc.

This is one reason why these conventions exist. cough GraphQL cough)

The thing that does CORS in (understandability-wise) is that the decision to send

preflights isn’t as straight-forward as checking the request’s verb (GET / PUT

etc.). There are cases when even a GET request can trigger a preflight, for example

if it tries to send a custom header (anything that isn’t Content-Type with some

allowed values). This is because functionality of these custom headers isn’t part

of any conventions, so it is hard to figure out what the server will do with it.

To err on the side of caution, the browser will preflight such requests. MDN’s CORS documentation

is a surprisingly good read to understand how browsers decide which requests to preflight.

Hopefully that page will feel a lot less dense now that you’ve read this post.

How does CORS actually help with security?

If it hasn’t been obvious so far, CORS only protects you if your client is willing

to respect the Access-Control-* headers. Web browsers are very strict about this,

but you can bypass CORS checks using curl. This isn’t a problem though. CORS isn’t

an end-all solution because it doesn’t have to be. If the primary goal here

is to stop dominos.com from sending a mutating request to yourbank.com, then

that has been accomplished. JS cannot bypass CORS in any way. It also cannot break

out of the browser’s shell. curl isn’t an attack vector because that indicates

that the attacker has physical access to your computer, which is very much not what

CORS is supposed to protect against.

TL;DR

Say you have a server on userstore.com. Authentication is irrelevant, but you do

not want just about anyone to be able to send you requests, or embed your content.

CORS exists to make this possible.

There are two kinds of requests an origin can make: simple ones that only read data

out of your server, and others that might mutate data (such as incrementing a

visitor counter). The browser looks at the request you’re trying to send, and makes

a decision about what kind of request it might be. It does so by inspecting the request

method, body and headers. For simple requests (that’s what they’re literally called),

it will send the request out to the host server, but it will check to see if the

server’s response has a header called Access-Control-Allow-Origin whose value

matches the origin the request was made from. If it does, then all’s well, the response

body is supplied to the JavaScript that initiated the request. If it doesn’t, the

JavaScript doesn’t get to read the response, and you see a CORS error that reads:

Access to fetch at 'http://userstore.com/users' from origin 'http://localhost:3000' has been blocked by CORS policy: No 'Access-Control-Allow-Origin' header is present on the requested resource. If an opaque response serves your needs, set the request's mode to 'no-cors' to fetch the resource with CORS disabled.

The important thing to realize is that the simple request did actually go out to your server, which responded. Since authorization isn’t a consideration, this is not harmful because it was just a read, after all. This is what the HTTP conversation might look like:

HEAD /users HTTP/1.1

Host: userstore.com

Origin: http://localhost:3000

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: http://localhost:3000

Content-Type: application/json

<Response-Body>However, if the browser thinks that the intended request might mutate state on

the host server, it actually sends out two requests, the first is called a preflight

request that is basically a description of the actual request. Your server is expected

to read this description and respond with a 2xx status code to allow the request,

or anything else to reject it. This preflight request uses the OPTIONS verb, and

this is what the request / response pair might look like:

OPTIONS /users HTTP/1.1

Host: http://userstore.com

Origin: http://localhost:3000

Access-Control-Request-Method: PUT

Access-Control-Request-Headers: User-Id

HTTP/1.1 204 No Content

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: http://localhost:3000

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: PUT

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: User-IdThe browser asks the server if a PUT verb (indicated by the Access-Control-Request-Method header)

on /users (indicated by the pathname of the OPTIONS request) is allowed from

the origin http://localhost:3000 (indicated by the Origin header) with the additional

header User-Id (indicated by the Access-Control-Request-Headers header).

If all these params are acceptable, the server responds, saying that the origin http://localhost:3000

(indicated by the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header) is allowed to send a PUT verb

(indicated by the Access-Control-Allow-Methods) on the requested path (/users in this case),

along with the additional headers User-Id (indicated by the Access-Control-Allow-Headers

header). The browser will then verify this response, and send out the actual PUT request

if all’s good. The PUT isn’t sent out at all if the server does not allow it!

How the browser decides if a request needs a preflight has a few edge cases — it is not as straight-forward as checking the request’s verb. These are documented pretty well in MDN’s CORS documentation, which is a great read regardless.

Conclusion

Hopefully this has demystified CORS for people reading! Most full-stack developers think CORS is an untameable beast, but I think that mostly comes from a place of ignorance. I was firmly in that camp too a couple of weeks ago. It really isn’t that bad.